Tuesday, September 27, 2005

Today, I made the fisrt noticeable progress during Kyudo keiko-practice. Mita-sensei approved of my technique with the practice rubber thingy, and he picked out the first yumi-bow- that I will be using. It is a ten-kilo bow, which means that it is a beginner's bow. It is important to get the form down with the beginner's bow before one can move to a higher tension bow. I still shake quite a bit when in Kai-full draw stance-even though it is only ten kilos. I am working on my form as well as learning how to focus my energy in my hara. It is important in Kyudo to expand the hara with each breath, and when the archer is ready for hanare-release-all of that stored ki should go into the shot. To accomplish this feat the movements between stances must be in harmony with the breath, and with complete relaxation. I have such a long way to go, but it is really fun to practice all of these things. I am definately looking forward to the day when I can shoot the arrow at the practice target even though it is only four feet away. I saw one other student reach that point, and on her very first shot she hit her forearm with the string, putting a large welt on her flesh, a worthy would I would say. I have a long way to go until my form is good enough to reach that point, but I am already showing the signs of future Kyudo calusses. It is all very exciting.

Saturday, September 24, 2005

Thursday, September 22, 2005

Kamagasaki: A Trip into the Uncomfortable

Kamagasaki is a section of Osaka that is not normally part of most people’s image of Japan. It is the largest slum, or economically depressed community in all of the country. There are more than 25,000 men in the low income bracket, which means that they are either homeless, or are living in low income housing. The only work that is available is day labor. Each day between 4:30 and 7:30 in the morning vans and trucks file into a labor assistance facility called Airin, and seek capable workers for mainly manual labor. On average, they offer approximately 2,700 jobs, a small number in comparison to the people in need. The employers post job descriptions and pay scales for the job. In some cases the employer will hire a recruiter to entice young strong workers. In those situations, the recruiter acquires a percentage of the worker’s pay, which is normally between 10,000 and 16,000 yen per day. In the US that would be considered sufficient wages to rise out of poverty, but with the high cost of living, inconsistent work, and overpriced deposits for housing in Japan that amount makes gaining economic status extremely difficult.

A major problem for the residents of Kamagasaki is the increasing aging population in Japan. The majority of the men living in the community are in their middle age or older. This makes it difficult to get a job requiring intensive physical labor. On top of that, not getting work lowers moral, which many resort to heavy drinking. Alcoholism contributes further to the difficulty of acquiring work because employers do not want workers who cannot perform in a satisfactory manner due to shaking, blurred vision, or nausea. On the second floor of the Airin building there were hundreds of men sleeping on the concrete in the late morning of a weekday with the smell of sweat and alcohol wafting through the air.

There were a few social programs committed to helping these men. One large nonprofit organization the group visited was committed to assisting the unemployed getting back on their feet. This organization provided meals, tight sleeping quarters, toilets, and shower facilities. They even offered 270 jobs a day in which workers maintain the upkeep of the community by sweeping, picking trash, and separating recyclables. They provided those jobs with the intent of helping those residents who could not acquire work with the day laborers. Most of these men had handicaps, were past middle-aged, or had problems with alcoholism. They received over 3,000 applications for these 270 jobs. In order to compensate, they put employees on a ten-day rotation, or in other words they work once every ten days. The pay for that work was 5,600 yen per day, a severely inadequate amount if that was the only work for the men. Unfortunately, the NPO was offering everything they could within their budget.

The affordable health facilities for the unemployed were inadequate as well. The one free hospital could hold only 130 patients. The need for more healthcare was so great that NPO’s provided special free housing for injured or ill residents. The shortage of healthcare is not due to too few hospitals, but to the discrimination and highly expensive costs at other facilities. On average, one night in a hospital costs over 5,000 yen, and when the administration or doctors find out where the patients are from the care ends up being half-assed, to put it bluntly.

Attending an East Asian Studies field trip in this community consisted of traveling from one social help organization to another while passing rickety venders, trash, offensive scents of urine, homely old men lingering in the street, and many other sights unthought-of in Japan. The guides, Mami-san and Brian Cloud, asked that the students not take pictures, or stare at the residents, but even after living in India for nine months where poverty, suffering, and deformities were prevalent it was a difficult task not to gawk. Even though there was such an obvious distinction between the American students wondering through the streets with wide open eyes of fear and discomfort and the hordes of unemployed men living their normal lives there was not a single incident of confrontation, or even negative vibes. The students were accepted with mainly uninterested notice except for a bare few who said hello, or, “where are you from?”

The last organization visited was an after-school program for underprivileged or learning disabled children. This place, like many other social work facilities in the community, was started by a Christian in the early sixties. The current director, Mami-san, was the wonderful woman who guided the class through the maze of streets, welfare facilities, and cardboard kiosks. She dedicated her work to the welfare of underprivileged children in her community. The mission with this program is to give those children a safe place to play, and socialize with adults and other children. She believed that a major problem with the treatment of the lower social classes, and disabled peoples in Japan was that they were separated from the larger community, and considered outcasts. That type of separation also creates difficulties for the underprivileged to interact with others in life. She provided that safe environment to teach people how to socialize with each other with acceptance and grace. It was truly beautiful to see someone with such an honorable and compassionate dream.

The last section of the expedition consisted of exploring the red-light district that was adjacent to Kamagasaki. This was perhaps the most dehumanizing aspect of the trip because of the displayed women selling their bodies to desperate men. Each stall had two women sitting, and waiting for the next customer, one scantily clad behind bright neon spotlights, and the other older with shrewd eyes staring the young western men down as they passed. It was one large city block lined with stall after stall advertising in kanji, “Beautiful Princess” and “Precious Jewel”. The group was told that until approximately one hundred years ago the area was surrounded by a twenty-foot wall imprisoning the young women indebted to the brothel owners, for one reason or another. There was still evidence of the wall, but there were stairs on one side, and an open gate on the other.

To say the least, the trip was a view of desperate situations that exist even in a strong economic country like Japan. It was a chance for the students to see suffering first hand, smell the offensive odor of stale urine, come into contact with social programs that work on the “getting your hands dirty” level, and finally realize the humanness and similarities of all people. These are folks that have come into bad times, but their situation should not be dealt with by thinking of their otherness. Humans need to feel the responsibility for each other and the world’s sustainability.

A major problem for the residents of Kamagasaki is the increasing aging population in Japan. The majority of the men living in the community are in their middle age or older. This makes it difficult to get a job requiring intensive physical labor. On top of that, not getting work lowers moral, which many resort to heavy drinking. Alcoholism contributes further to the difficulty of acquiring work because employers do not want workers who cannot perform in a satisfactory manner due to shaking, blurred vision, or nausea. On the second floor of the Airin building there were hundreds of men sleeping on the concrete in the late morning of a weekday with the smell of sweat and alcohol wafting through the air.

There were a few social programs committed to helping these men. One large nonprofit organization the group visited was committed to assisting the unemployed getting back on their feet. This organization provided meals, tight sleeping quarters, toilets, and shower facilities. They even offered 270 jobs a day in which workers maintain the upkeep of the community by sweeping, picking trash, and separating recyclables. They provided those jobs with the intent of helping those residents who could not acquire work with the day laborers. Most of these men had handicaps, were past middle-aged, or had problems with alcoholism. They received over 3,000 applications for these 270 jobs. In order to compensate, they put employees on a ten-day rotation, or in other words they work once every ten days. The pay for that work was 5,600 yen per day, a severely inadequate amount if that was the only work for the men. Unfortunately, the NPO was offering everything they could within their budget.

The affordable health facilities for the unemployed were inadequate as well. The one free hospital could hold only 130 patients. The need for more healthcare was so great that NPO’s provided special free housing for injured or ill residents. The shortage of healthcare is not due to too few hospitals, but to the discrimination and highly expensive costs at other facilities. On average, one night in a hospital costs over 5,000 yen, and when the administration or doctors find out where the patients are from the care ends up being half-assed, to put it bluntly.

Attending an East Asian Studies field trip in this community consisted of traveling from one social help organization to another while passing rickety venders, trash, offensive scents of urine, homely old men lingering in the street, and many other sights unthought-of in Japan. The guides, Mami-san and Brian Cloud, asked that the students not take pictures, or stare at the residents, but even after living in India for nine months where poverty, suffering, and deformities were prevalent it was a difficult task not to gawk. Even though there was such an obvious distinction between the American students wondering through the streets with wide open eyes of fear and discomfort and the hordes of unemployed men living their normal lives there was not a single incident of confrontation, or even negative vibes. The students were accepted with mainly uninterested notice except for a bare few who said hello, or, “where are you from?”

The last organization visited was an after-school program for underprivileged or learning disabled children. This place, like many other social work facilities in the community, was started by a Christian in the early sixties. The current director, Mami-san, was the wonderful woman who guided the class through the maze of streets, welfare facilities, and cardboard kiosks. She dedicated her work to the welfare of underprivileged children in her community. The mission with this program is to give those children a safe place to play, and socialize with adults and other children. She believed that a major problem with the treatment of the lower social classes, and disabled peoples in Japan was that they were separated from the larger community, and considered outcasts. That type of separation also creates difficulties for the underprivileged to interact with others in life. She provided that safe environment to teach people how to socialize with each other with acceptance and grace. It was truly beautiful to see someone with such an honorable and compassionate dream.

The last section of the expedition consisted of exploring the red-light district that was adjacent to Kamagasaki. This was perhaps the most dehumanizing aspect of the trip because of the displayed women selling their bodies to desperate men. Each stall had two women sitting, and waiting for the next customer, one scantily clad behind bright neon spotlights, and the other older with shrewd eyes staring the young western men down as they passed. It was one large city block lined with stall after stall advertising in kanji, “Beautiful Princess” and “Precious Jewel”. The group was told that until approximately one hundred years ago the area was surrounded by a twenty-foot wall imprisoning the young women indebted to the brothel owners, for one reason or another. There was still evidence of the wall, but there were stairs on one side, and an open gate on the other.

To say the least, the trip was a view of desperate situations that exist even in a strong economic country like Japan. It was a chance for the students to see suffering first hand, smell the offensive odor of stale urine, come into contact with social programs that work on the “getting your hands dirty” level, and finally realize the humanness and similarities of all people. These are folks that have come into bad times, but their situation should not be dealt with by thinking of their otherness. Humans need to feel the responsibility for each other and the world’s sustainability.

Wednesday, September 21, 2005

Updates

It has been a little while since I have posted anything, so I thought that I should give a run down on my experiences in Japan because a lot has happened. Last week I started going to a Kyudo dojo, which is a school for Zen archery. The first two hours on Friday were spent trying to convince the sensei that I should be his student. This was needed because of the short time that I will be studying. He said that it normally takes one year of study to reach the level in which one is able to properly shoot at the target, which is twenty-eight meters away. He said that the previous westerners that have studied there had been under the impression that they could become masters quickly. "This dojo is very strict and prestigious," said Seto, the translator. I was not going to take no for an answer, and told him that I wanted to study kyudo in order to improve my focus, and discipline for my life rather than become a master at kyudo. He thought that it was a sufficient answer, and had Seto help me fill out the application form. On saturday, I went back to watch a tournament that happens once a month between the higher level practitioners of the dojo. It was fabulous to watch the grace of the participants, especially the women. i think that this art requires a calm grace that women naturally have. The sensei's are all men, and they were the winners, but I thought the women had a step ahead in the beauty of the shot. Yesterday was my first lesson. I first learned the proper ways to sit, bow, and pray to the kami. Next, I was taught the hassetsu, or eight stages of shooting. I was told to memorize each one, and be able to bring them forth naturally. Then, I practiced drawing the practice rubber band back. My form was terrible! I was told that I need to breath from my center because that is where the strength comes for the motion. He said that all of my ki is up in my chest, and not down in my tantien. With each breath the stomach should expand without shrinking on the exhalation. This is not so easy. "In kyudo, it is very important to find a rhythm," said Chen, a Japanese born Chinese man who so kindly explained the sensei's words. After that I tried and tried, but have yet to pull the band back without shrugging my shoulders or arching my back.

On saturday morning, I made my second visit to the Elder home, Hanasaka-so where I am doing service. I received the same type of applause upon arrival, and jumped right into attempting communication with my limited vocabulary. There were two young employees there who spoke some english, so they translated the things I did not know. After another delicious lunch of fried tofu stuffed withmushrooms and veggies, cooked napa cabbage, cucumber, fish, and daikon salad, miso soup, potato salad with chives and raisins, and rice with chesnuts, I started giving massage. I gave ten massages between 12:30 and 4PM. It was tiring, but they were so happy to be touched. One lady had an adhesed shoulder girdle, which just needed a little stretching and touch. After the massage she could lift her arm above her head, and was so happy that she gave me a hug with numerous arigatou's. I wish that every problem was that easy to help. Kobayashi-san said that I did a great job, and insisted that she pay me for my work from then on. I refused, but she would not take no for an answer. She even told my school that she would not take no for an answer. It will not be much, but I am very happy for the help. It will be more than enough to cover the cost of kyudo lessons, which is a relief because of the high cost of living.

On Sunday, Dan and I went on another hike, which was much easier this time. We went up Daimonji, which is a mountain overlooking Kyoto, and has a giant kanji for "big" The symbol has many fire pits all along it which are lit during festivals. On the way up we came upon a waterfall that has a shower stall built of stone at the bottom. I took off my cloths, and jumped in, cool and refreshing! I later learned that spot is a place of pilgrimage for monks all over Kyoto to purify themselves in the dead of winter. supposedly they stand under the falls, and pray with fridged water pouring over them. Kind of like the sacred polar bear club, I guess. Later on in the hike my camera broke, which really sucks because I have been averaging about twenty photos a day. It puts a damper on the visual documentation, but atleast i was smart enough to save the receipt and warrenty. I am going to try and find a cheep replacement in the meantime.

lastly, monday was our final in survival japanese. It was long and arduous, but I got a 98%!!! I think that is my best grade ever in a language test. Shit I kyudo right now! got to go.

On saturday morning, I made my second visit to the Elder home, Hanasaka-so where I am doing service. I received the same type of applause upon arrival, and jumped right into attempting communication with my limited vocabulary. There were two young employees there who spoke some english, so they translated the things I did not know. After another delicious lunch of fried tofu stuffed withmushrooms and veggies, cooked napa cabbage, cucumber, fish, and daikon salad, miso soup, potato salad with chives and raisins, and rice with chesnuts, I started giving massage. I gave ten massages between 12:30 and 4PM. It was tiring, but they were so happy to be touched. One lady had an adhesed shoulder girdle, which just needed a little stretching and touch. After the massage she could lift her arm above her head, and was so happy that she gave me a hug with numerous arigatou's. I wish that every problem was that easy to help. Kobayashi-san said that I did a great job, and insisted that she pay me for my work from then on. I refused, but she would not take no for an answer. She even told my school that she would not take no for an answer. It will not be much, but I am very happy for the help. It will be more than enough to cover the cost of kyudo lessons, which is a relief because of the high cost of living.

On Sunday, Dan and I went on another hike, which was much easier this time. We went up Daimonji, which is a mountain overlooking Kyoto, and has a giant kanji for "big" The symbol has many fire pits all along it which are lit during festivals. On the way up we came upon a waterfall that has a shower stall built of stone at the bottom. I took off my cloths, and jumped in, cool and refreshing! I later learned that spot is a place of pilgrimage for monks all over Kyoto to purify themselves in the dead of winter. supposedly they stand under the falls, and pray with fridged water pouring over them. Kind of like the sacred polar bear club, I guess. Later on in the hike my camera broke, which really sucks because I have been averaging about twenty photos a day. It puts a damper on the visual documentation, but atleast i was smart enough to save the receipt and warrenty. I am going to try and find a cheep replacement in the meantime.

lastly, monday was our final in survival japanese. It was long and arduous, but I got a 98%!!! I think that is my best grade ever in a language test. Shit I kyudo right now! got to go.

Sunday, September 18, 2005

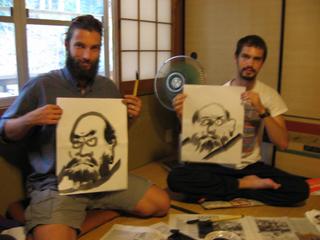

Happy Harvest Moon

I have been very busy lately with Japanese class, the elderly home, kyudo practice, and writing papers. I do not have any long stories of my adventures to add right now, but here are a few pictures taken lately. They are of our Sumie-ink painting class, a kyudo tournament, and some kirpuscular rays in the Kyoto sky. Enjoy.

Monday, September 12, 2005

First Experience with Japanese Elder Care

Today, I was invited to go along with my fellow classmates, Chris and Maya, to an elderly home, and observe Chris perform a concert on the traditional Japanese harp, the Koto. Their landlord, Ms. Kobayashi is also the owner of the elderly home. I had my advisor, Aaron, tell her that I was interested in doing a service project at the elderly home, so I was asked to give a demonstration massage after the concert. I was not expecting to perform, but only to be introduced to the members as someone who would offer massage in the future. The whole experience of the visit was certainly an introduction to elderly care in Japan because of the great contrast with any of the homes I had previously visited. Everything from the food, to the employees, to the facilities, and the community was strangely new.

Kobayashi-san was an amazingly sweet woman with beautiful, compassionate, and patient eyes. She took us, Chris, Maya (Chris’s wife), and I, on a tour of the outskirts of Kyoto, which consisted of gorgeous rice fields, gardens, and lakes surrounded by mountains. The rice paddies were glowing fluorescent green with vitality. She spoke with an almost infinite amount of patience; although, I could understand very little. Chris did his best to be the translator between us. I did my best to explain my interest in elder care, but I think that more understanding will have to come out of my commitment to service.

The members of the home greeted us with the utmost warmth and hospitality when we walked in the door. We were ushered over to a table with a spread of food that could not be compared against elderly homes in the states. There was miso soup, fried tofu filled with cheese and topped with sauce and sprouts, orange squash with tender ricotta style cheese, a carrot, asparagus, and raisin salad, and cool oolong tea. It was delicious and delicate, and definitely the best miso soup that I have ever tasted.

After eating our fill, Kobayashi-san offered a room for Chris to tune his Koto, and gave Maya and I a tour of the facility. It was elegantly simplistic, yet more than adequate in amenities. There was even an outdoor fire pit, and garden area, which had okra, tomatoes, blueberries, shiso, mint, eggplant, a persimmon tree, and more. I could not have been more excited about the connection to nature. It was the type of place that any of us would like to end up in when we get old.

When returning to the common room we saw that it had been transformed from a dining space to a concert hall with open floor space, golden folding screens, and a flowering plant. Chris was given the floor, and he performed beautifully to my untrained ears, anyway. His last number was what I thought must have been the national anthem, or something like it because everyone was singing along. They actually had him do four encores with everyone singing!

Next, I was asked to introduce myself, which meant I actually had to use most of my new phrases from survival Japanese. Chris did his best to fill in the parts that was not in my repertoire. I ended by asking how many people had ever received massage, which was answered by about five tentative hands. Then Kobayashi-san asked if I would give a demonstration massage, so they all could see what exactly it was that I did. I accepted, rather shyly, and one of the men was asked if he would like to be the guinea pig. Chris told me later that he said, “That sounds very nice, but I don’t think it is for me.” After a little hesitation, one lady volunteered, which I noticed was one of the people whose hand had been raised in response to my question. I gave her about a ten-minute shoulder, head, and hand massage. She seemed to love it, and said that she was filled with good feeling afterwards (translated by Chris). I also think it was a success because I saw a lady massaging her own arm after I did the demonstration.

The formality of the introductions and concert were given up after the demonstration, and the real fun began. The employees handed out sheets with songs on them, and everyone took part in singing a couple different numbers. One of them was a song about rowing down a river, and it was accompanied by rowing motions with yellow scarves. It was a beautiful sight to see everyone, including a woman of 97 years, singing and rowing along. The other song that they sang was a drinking song traditionally sung by geisha. People seemed to really enjoy that one as you might have guessed.

Before we left they served tea, which consisted of sliced cantaloupe, a sweet bean candy, and a grape that was meticulously opened to the shape of a flower, and quartered. Those snack were accompanied by cool oolong tea. As I said before, the quality of food was outstanding, which was a relief to see in a place of our elders.

Throughout the experience I was continually surprised by the quality of treatment that the clients received. I look forward to continuing this exploration of Japanese Elder Care next Saturday when I return to build relationships with these folks, and offer a service of massage and anything else asked of me.

Kobayashi-san was an amazingly sweet woman with beautiful, compassionate, and patient eyes. She took us, Chris, Maya (Chris’s wife), and I, on a tour of the outskirts of Kyoto, which consisted of gorgeous rice fields, gardens, and lakes surrounded by mountains. The rice paddies were glowing fluorescent green with vitality. She spoke with an almost infinite amount of patience; although, I could understand very little. Chris did his best to be the translator between us. I did my best to explain my interest in elder care, but I think that more understanding will have to come out of my commitment to service.

The members of the home greeted us with the utmost warmth and hospitality when we walked in the door. We were ushered over to a table with a spread of food that could not be compared against elderly homes in the states. There was miso soup, fried tofu filled with cheese and topped with sauce and sprouts, orange squash with tender ricotta style cheese, a carrot, asparagus, and raisin salad, and cool oolong tea. It was delicious and delicate, and definitely the best miso soup that I have ever tasted.

After eating our fill, Kobayashi-san offered a room for Chris to tune his Koto, and gave Maya and I a tour of the facility. It was elegantly simplistic, yet more than adequate in amenities. There was even an outdoor fire pit, and garden area, which had okra, tomatoes, blueberries, shiso, mint, eggplant, a persimmon tree, and more. I could not have been more excited about the connection to nature. It was the type of place that any of us would like to end up in when we get old.

When returning to the common room we saw that it had been transformed from a dining space to a concert hall with open floor space, golden folding screens, and a flowering plant. Chris was given the floor, and he performed beautifully to my untrained ears, anyway. His last number was what I thought must have been the national anthem, or something like it because everyone was singing along. They actually had him do four encores with everyone singing!

Next, I was asked to introduce myself, which meant I actually had to use most of my new phrases from survival Japanese. Chris did his best to fill in the parts that was not in my repertoire. I ended by asking how many people had ever received massage, which was answered by about five tentative hands. Then Kobayashi-san asked if I would give a demonstration massage, so they all could see what exactly it was that I did. I accepted, rather shyly, and one of the men was asked if he would like to be the guinea pig. Chris told me later that he said, “That sounds very nice, but I don’t think it is for me.” After a little hesitation, one lady volunteered, which I noticed was one of the people whose hand had been raised in response to my question. I gave her about a ten-minute shoulder, head, and hand massage. She seemed to love it, and said that she was filled with good feeling afterwards (translated by Chris). I also think it was a success because I saw a lady massaging her own arm after I did the demonstration.

The formality of the introductions and concert were given up after the demonstration, and the real fun began. The employees handed out sheets with songs on them, and everyone took part in singing a couple different numbers. One of them was a song about rowing down a river, and it was accompanied by rowing motions with yellow scarves. It was a beautiful sight to see everyone, including a woman of 97 years, singing and rowing along. The other song that they sang was a drinking song traditionally sung by geisha. People seemed to really enjoy that one as you might have guessed.

Before we left they served tea, which consisted of sliced cantaloupe, a sweet bean candy, and a grape that was meticulously opened to the shape of a flower, and quartered. Those snack were accompanied by cool oolong tea. As I said before, the quality of food was outstanding, which was a relief to see in a place of our elders.

Throughout the experience I was continually surprised by the quality of treatment that the clients received. I look forward to continuing this exploration of Japanese Elder Care next Saturday when I return to build relationships with these folks, and offer a service of massage and anything else asked of me.

Saturday, September 10, 2005

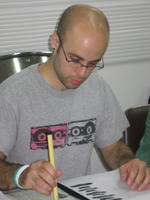

An Exploration of Shodo, Japanese Calligraphy

The first Area Studies class of the semester was an introduction to Shodo, the art of calligraphy. This type of calligraphy is not the type that we know of in the west; although, there are some similarities such as learning about precise hand-eye coordination. The other similarity is that it is comparable to the more ancient style of writing. A number one difference comes when considering the language from which both types of calligraphy are derived. In the hand-out that we received prior to the class there is an explanation of the language differences The paper explains the profundity of this type of calligraphy as such: Of the three different kana (alphabets) Kanji is the one preferred and most frequently used in Shodo. The other two kana, hiragana and katakana, are used in similar manners as our alphabet in that they are phonogrammic, or the symbols correspond directly to a sound. Kanji, on the other hand, are ideographic, which means that they simply convey meaning. The English language as well as other western languages is also phonogrammic, which means that the same difference exists between English calligraphy and Shodo as the former two kana and Kanji. This distinction can lead to the understanding that the art form is more than simply technical mastery, but has intellectual and spiritual depth. To convey this idea there should first be a little more explanation of the background of kanji, the practice of Shodo, and my experience of attempting Shodo.

Kanji was brought to Japan from the motherland, China. As explained earlier, kanji, the Chinese written language is made up of ideographic characters rather than phonographic symbols. Consequently, the order of comprehension does not have to go from symbol to sound to meaning, but simply from symbol to meaning. This is where the real depth of the art can be understood because the symbols are meant to be innately evocative. The handout had the example of mountain in the form of English versus Kanji, which in English is m-o-u-n-t-a-i-n, and the meaning is then understood by recognizing the sound. In kanji the sound is yama, but the symbol represents the idea of a mountain, so it is supposed have the innate meaning of mountain. In explaining the practice one might be able to understand the depth of why this is such a major difference.

A Shodo practitioner does not simply sit down, and start writing/painting. There are specific meditative practices that are involved when attempting Shodo. The handout explains it as such: “The calligrapher’s mind must be clear and relaxed-meditative. He must be centered, breathing deeply from his hara, the gut and center of ki. Then, he allows the idea of the kanji he is about to paint to enter his mind. He does not think of the form of the character yet; first he imagines and feels the idea that it represents. His mind becomes, for example, the mountain, and only then does he execute with precision and spirit the simple character of yama.” (Page 4) Just in observing the process of the practice of Shodo one might start to understand the depth of how each different person may interpret the symbol in various ways even though it is only one symbol with specified stroke orders.

The paper denotes the common misunderstanding that westerners may have about the creativity in Shodo. The differences in ideas about creativity are quite large between the east and west because in the common western arts there is allowance for “an infinite possibility of subject matter.” (Page 3) In Shodo, and other eastern arts, there is a uniformity of the medium and content of the art. The paper explains, “The uniformity of content actually deepens the creativity required to excel in shodo. Technical mastery with the brush is only the first step. For the image to come alive, the calligrapher must imbue the image something of his soul, his creative energy.” (Page 3) This conflict between types of creative energy can be put simply, freedom from form versus freedom in form. Both are valid, and both are incredibly hard to achieve.

Our class on Shodo consisted of receiving a very simple introduction to the materials, the beginning brush strokes, and a few examples of kanji of the elements, fire, water, wind, and earth. Our teacher, Oko, was a soft-spoken woman with an amazingly steady hand, and an encouraging demeanor. I spent the first two hours trying to do the basic brush strokes, which were much, much harder than they appeared. Even when painting simple vertical and horizontal strokes I had difficulty. Next, I attempted writing my name in katakana, and lastly I painted the kanji of the elements. I felt strong connections to the kanji of wind and water, which makes sense due to my Aquarian lineage. Having read and understood the guidelines for identifying quality shodo, I was not able to produce anything that I found satisfactory, but it was fun to be in art class again. When later I was telling one of my classmates about my difficulty, she reminded me that becoming good at shodo not only requires technical mastery, but years of mental discipline. I felt a little better after being reminded of that, and could reside in the simple enjoyment of participating in such an ancient art.

Kanji was brought to Japan from the motherland, China. As explained earlier, kanji, the Chinese written language is made up of ideographic characters rather than phonographic symbols. Consequently, the order of comprehension does not have to go from symbol to sound to meaning, but simply from symbol to meaning. This is where the real depth of the art can be understood because the symbols are meant to be innately evocative. The handout had the example of mountain in the form of English versus Kanji, which in English is m-o-u-n-t-a-i-n, and the meaning is then understood by recognizing the sound. In kanji the sound is yama, but the symbol represents the idea of a mountain, so it is supposed have the innate meaning of mountain. In explaining the practice one might be able to understand the depth of why this is such a major difference.

A Shodo practitioner does not simply sit down, and start writing/painting. There are specific meditative practices that are involved when attempting Shodo. The handout explains it as such: “The calligrapher’s mind must be clear and relaxed-meditative. He must be centered, breathing deeply from his hara, the gut and center of ki. Then, he allows the idea of the kanji he is about to paint to enter his mind. He does not think of the form of the character yet; first he imagines and feels the idea that it represents. His mind becomes, for example, the mountain, and only then does he execute with precision and spirit the simple character of yama.” (Page 4) Just in observing the process of the practice of Shodo one might start to understand the depth of how each different person may interpret the symbol in various ways even though it is only one symbol with specified stroke orders.

The paper denotes the common misunderstanding that westerners may have about the creativity in Shodo. The differences in ideas about creativity are quite large between the east and west because in the common western arts there is allowance for “an infinite possibility of subject matter.” (Page 3) In Shodo, and other eastern arts, there is a uniformity of the medium and content of the art. The paper explains, “The uniformity of content actually deepens the creativity required to excel in shodo. Technical mastery with the brush is only the first step. For the image to come alive, the calligrapher must imbue the image something of his soul, his creative energy.” (Page 3) This conflict between types of creative energy can be put simply, freedom from form versus freedom in form. Both are valid, and both are incredibly hard to achieve.

Our class on Shodo consisted of receiving a very simple introduction to the materials, the beginning brush strokes, and a few examples of kanji of the elements, fire, water, wind, and earth. Our teacher, Oko, was a soft-spoken woman with an amazingly steady hand, and an encouraging demeanor. I spent the first two hours trying to do the basic brush strokes, which were much, much harder than they appeared. Even when painting simple vertical and horizontal strokes I had difficulty. Next, I attempted writing my name in katakana, and lastly I painted the kanji of the elements. I felt strong connections to the kanji of wind and water, which makes sense due to my Aquarian lineage. Having read and understood the guidelines for identifying quality shodo, I was not able to produce anything that I found satisfactory, but it was fun to be in art class again. When later I was telling one of my classmates about my difficulty, she reminded me that becoming good at shodo not only requires technical mastery, but years of mental discipline. I felt a little better after being reminded of that, and could reside in the simple enjoyment of participating in such an ancient art.

Tuesday, September 06, 2005

Picture of the Day

It has been raining for the past three days, so travelling is somewhat limited, but I have been going to class and went out to dinner with some students last evening. This picture was taken yesterday morning. I heard some sort of chanting and went outside to see what was happening. There were several monks walking up and down the street calling out something in Japanese. I wonder what they were saying. Plus, it was raining very hard at the time.

Monday, September 05, 2005

Weekend Adventures

One of my friends from CU is here in Japan, and he has been emailing me since he got here. On Saturday evening he showed up in Kyoto, and we decided that we would check out the nightlife of the town. I had heard about a Reggae bar called Rub a’ Dub. I had gotten directions from this Japanese girl who spoke very good English. The only problem was that the directions were a little erroneous. We spent about an hour and a half looking for the place, and asking directions until we met someone who knew of the reggae bar. It was down in a basement with grungy walls. The bar was covered with shanty style corregated metal roofing. The music was great, and they even had jerk chicken on the menu. We left the bar at 11:05, and soon found out that the buses stop running at 10:46. We ended up walking about five miles back to the dorm.

The next morning we went out for a hike that was described in this book called Hiking in Japan. It was listed as easy, so I thought that it would be a good one to start with. We took a buss from Kyoto up to Kiyotaki, a small village just northwest of the city. The town is in a very narrow valley, along a river, and has many traditional style homes and inns. After walking through the town the trail started up the hill, and up, and up. We walked 4.5 kilometers straight up this mountain called Atago-san. At the top was a beautiful Buddhist temple that seemed to have the theme of wild boars, inuishi. The carpentry was exquisite with carvings of animals, and gorgeous timber-framing. The whole temple smelled of cedar wood.The top of the mountain was cold, rainy, and in the clouds. There were virgin cedars all around, and some that were about ten feet in circumference. After visiting the temple we asked the local monk which way the next part of the trail was, and he answered by telling us that it was very dangerous with a narrow trail, many connecting trails, and bears. I had prayed for our trip to be safe, so I took his warning as an omen not to try and go the next 10K down the other side of the mountain. Plus, by that time the rain was coming down in torrents, so headed down the way that we had come. Once down the mountain we took a lovely swim in the river, which had numerous schools of fish, and even a turtle. The hike was hard, but it made me excited for more hiking in Japan.

Thursday, September 01, 2005

A Response to the Issue of Cultural Contradiction

One of the last comments included the anonymous person's fear of Japan because of the contradiction of oppression and beauty. I feel that in every culture there are inherent contradictions In India there was a big thing about purity and pollution being an important awareness, but people would spit, shit, piss, and litter all over public places. On one occasion I went to B.R. hills, which is a tribal region in southern India. The guide took our class to this sacred grove deep in the forest where there was a three-thousand year old tree. People from that tribe had been worshiping Shive there for over a thousand years, but there was thrash littered on the forest floor not a hundred meters away.

Another scenario is to look at women and women's rights in the USA and also how foreigners think of US women. I mean, we seem to have come so far with putting women on an equal playing field, but we just contradict that with objectifying them through thier anatomy and sexual appeal. Or we make it so hard for women to feel comfortable with thier bodies and body wieght by having so much media and advertisements that tell women how they should look. I feel that many american women have lost thier dignity by following the social standards of vanity. I distinctly remember being in India with my mother, and listening to her say, "I am never wearing khaki shorts again." This was after seeing a group of western tourists walking by. The women in India are more oppressed than in any other place than I have been, but they carry themselves with so much dignity and beauty that they look good no matter what shape and size they are. I have not yet been to any middle eastern countries yet, but that is my experience so far.

The whole point here is that yes there are inherent contradictions, but if you limit yourself from visiting a culture because you don't agree with a certain part of it then you are just being hipocritical and narrow-minded. Life is about seeing, and not seeing good or bad, but just seeing (and experiencing). But, you can choose what you want to do.

One more thing, I met a girl yesterday named Keiko, and she had spent one year in Ohio for an exchange program. She said that in Japan people think of America being this perfect place because so many of them have visited NY and LA. She said that the truth is that you don't really see america unless you get into middle america and the more blue collar areas. I thought that she was really insightful with that observation. I asked her what her favorite and least favorite things about the US were. She said the beauty and diversity were her favorite things, and people being two-faced was her least favorite thing. How about that contradiction?

Another scenario is to look at women and women's rights in the USA and also how foreigners think of US women. I mean, we seem to have come so far with putting women on an equal playing field, but we just contradict that with objectifying them through thier anatomy and sexual appeal. Or we make it so hard for women to feel comfortable with thier bodies and body wieght by having so much media and advertisements that tell women how they should look. I feel that many american women have lost thier dignity by following the social standards of vanity. I distinctly remember being in India with my mother, and listening to her say, "I am never wearing khaki shorts again." This was after seeing a group of western tourists walking by. The women in India are more oppressed than in any other place than I have been, but they carry themselves with so much dignity and beauty that they look good no matter what shape and size they are. I have not yet been to any middle eastern countries yet, but that is my experience so far.

The whole point here is that yes there are inherent contradictions, but if you limit yourself from visiting a culture because you don't agree with a certain part of it then you are just being hipocritical and narrow-minded. Life is about seeing, and not seeing good or bad, but just seeing (and experiencing). But, you can choose what you want to do.

One more thing, I met a girl yesterday named Keiko, and she had spent one year in Ohio for an exchange program. She said that in Japan people think of America being this perfect place because so many of them have visited NY and LA. She said that the truth is that you don't really see america unless you get into middle america and the more blue collar areas. I thought that she was really insightful with that observation. I asked her what her favorite and least favorite things about the US were. She said the beauty and diversity were her favorite things, and people being two-faced was her least favorite thing. How about that contradiction?

Touring Temples

The last few days have been spent touring around Kyoto. One of our assignments before the semester starts is to follow specified routes around the city to familiarize ourselves. Yesterday a couple of my dormmates and I went on a tour that involved visiting two temples, and walking down Testugaku no Michi (the philosopher's path) the latter is a major part of Kyoto's fame because it is a path beside a canal lined with cherry trees. In the the spring it is supposed to glow with cherry blossums. At this time of year i found the two temples that we visited to be much more beautiful because of the exquisitely manicured gardens and the stunning archetecture. I am definately the most facinated when visiting these places. the city is a little less exciting, but shopping for and eating food is also really fun and engaging. Well, I think that the pictures will say much more than I can explain.